Q&A With Author Ruben Degollado

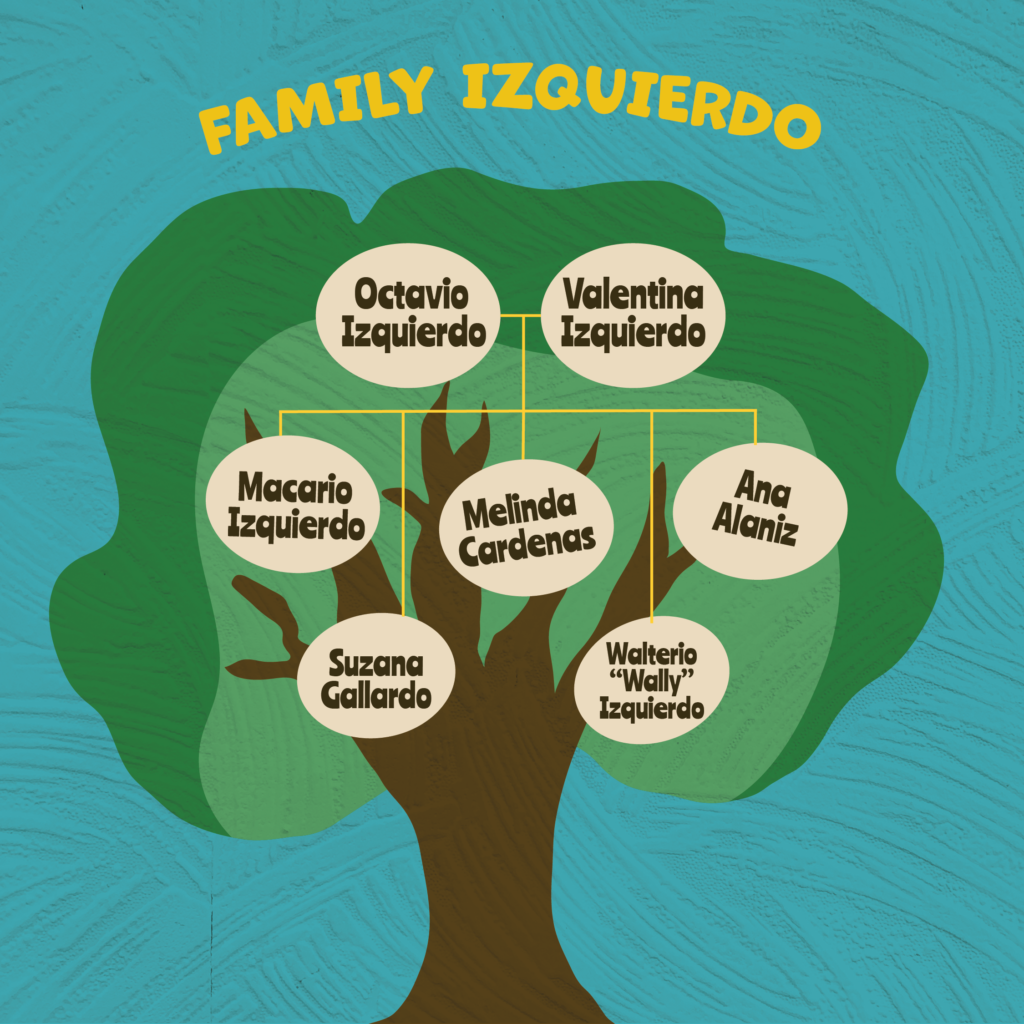

“The Family Izquierdo” is an epic that tells the story of a family plagued by the whispers of a curse for three generations. Originally a collection of short stories, Degollado weaves the lives of the Izquierdo’s together in a cultural mosaic. The story takes place in the neighborhoods of McAllen. It references people and places in the collective, cultural memory. Degollado writes in specific touchstones, values and voices that live within the mezcla of deep South Texas. “The Family Izquierdo” is a love letter, a prayer and an incantation that takes the faces and the voices known, breathing life into them. Pulse spoke with author Ruben Degollado to hear about his background, the writing process and what it takes to be a writer.

Can you tell us a little bit about your background?

“I was born in Indiana but my family has been in [the] Rio Grande Valley for generations. … I was born up there with my older brother and then we moved back to McAllen. So, I lived in McAllen for most of my life. I moved away to get married, moved away to Florida and Oregon. Alongside that … I got an education at UTPA. … I’m a legacy alum. I got my masters in Educational Administration at Lewis and Clark College. I was a teacher, became an assistant principal, then a principal. I moved back. I’ve been a number of things since I moved back but also [an] administrator. I worked at [a] church as a children’s pastor, worked at Region One as a director of school improvement. Now, I’m a consultant and I write. So, that’s a little bit about the background but I mean, mainly when I think about my background and who I am and where I’m from … I’m very much a Valley person. If you’ve lived in the Valley, anybody who lived in the Valley, they move away a lot of times and end up moving back and that’s my story.”

How did you arrive at [“The Family Izquierdo”]? Was it always about this family?

“Somewhere behind me on my bookshelf is the first appearance of the Family Izquierdo. I started writing short stories while I was at UTPA and then I wrote the first Izquierdo story in … 1995, 1996. It was based off of some family lore that I had heard. So, I wrote the story and then what ended up happening was I tried to experiment with other things. I tried to experiment with other stories and other settings and people but what I ended up doing was I kept coming back to this one family. So, I would write a story about one set of parents and then I would write a story about another tia that may appear in one of the stories. I kept going, kept going, kept going … what I was doing at the time that I didn’t know, I was creating this whole fictional universe of this family. This proud family living in McAllen during the 80s and the 90s. Of course, having arrived to McAllen much sooner with the grandparents. So, that’s how I did it. When you read “The Family Izquierdo,” what people don’t know is for authors a lot of times they’ll sit down. They will say, ‘Okay for the next year, two years, maybe three years, I’m gonna write this book.’ When I wrote the stories I never initially intended it to be a book and then, when I got probably about 13 stories in, I found that all of them were interlocking and I was actually writing a novel and I didn’t know it. … Each of the chapters are self-inclusive. Telling a story about one or two family members, but they all dovetail into telling a larger story about this family who has been cursed by a jealous neighbor. … Keeping that in mind, the book took me about, I want to say about 25 years, 20 years or so to write. Maybe about 25 years to actually get published. So, [a] very long time that I’ve been writing those stories. People when they’ve read it they go, ‘You really poured your heart on heart out on every page.’ Well, I’m like ‘That’s half of my life right now.’… I spent all that time writing about this family and I told you I lived in Oregon for a number of years. Most of the stuff that I wrote about the family was actually when I lived in Oregon. I mention this often but James Joyce, the inspiration for what I was doing, and I didn’t know I was doing at the time, was [from] the book “Dubliners.” It’s a collection of short stories set in Dublin. When James Joyce wrote that collection … my favorite book probably. He was … in Prague. He wasn’t in Dublin. He wasn’t in Ireland. But in interviews he had said that he saw Dublin more clearly when he was away from it. That’s what I saw. I saw McAllen more clearly, being away from it.”

So, you mentioned “Dubliners” and I see it in movies where a city becomes a main character. How did you kind of build a city with words?

“That’s an interesting question. I’ve never been asked that before. So, thank you for that. I would say the Valley in general is a character in all of my work. You could set the stories in California, in El Paso, but I made it so specific to McAllen. The way I did that, the way I created it is I used very specific details. So, there’s no other author–I read everything, I’m not bragging, I’m saying I’ve looked, but there’s no other author out there that writes about McAllen like I do because when I write about McAllen, when I’ve read anything that’s set in McAllen, it’s not specific. So, I mentioned places that people who live there know about: Barrio La Zavala, South McAllen. I mentioned stores that no longer exist, restaurants that no longer exist, that only exist in our collective memories as people who live in McAllen. Even the fact that I reference it ‘Ma-ca-len.’ That’s a way of [pronouncing] the city that a lot of people don’t know. They don’t know that here some people say ‘Ma-ca-lan’, or they used to call it that more so than the McAllen itself. ‘Ma-ca-lan’ and they spread it out. So, that’s how I approached it and my hope in doing that was that I’m writing a story about family dynamics, about loss, about forgiveness, redemption that I hope is universal to everyone reading the story. I’m writing to my people from the Rio Grande Valley. So, the distinction there is that it’s a story for everybody. When you read La Zavala, when you read very culturally specific, regionally specific words and language that are not Spanish, they’re just kind of some mezcla of language together. Somebody from here is going to get it. So, I’m writing it to them so that they can say, ‘Oh, I feel seen … I had not heard that, I had not seen that on the page.’ Words [such as], fisgona, borlote, chocante, all these words that are very specific to when we speak. I’m sure you hear them [in] other places, but we have a certain connection to words [such as those] and places that have never been seen before in fiction.”

Your novel is made up of interconnected stories. How did you stitch them together? How did you find the structure?

“Oh, wow. That’s a great question. What I mentioned earlier was I wrote them as stories and when my editor looked at them … because we initially said it’s a collection of short stories. … [She said] … ‘You’re telling one story, how do we just move away from it being a collection and into a novel. Because it is a novel. How do you do that?’ So, what I ended up doing, there’s these vignettes that separate the section. Here’s six or seven vignettes and those vignettes are structured in such a way that they’re in the more distant past and they’re dealing with Papa Tavo and Valentina. In those vignettes you see a connection from the past to the present story that’s being told. So, for example, there’s a scene where Papa Tavo and Maggie, the little girl. She’s a little girl at the time, they cut a special needs neighbor’s hair because nobody in town is able to cut his hair. You see this scene of Maggie becoming [a hairstylist]. She’s got a gift for it. Her father has taught her how to cut hair. She’s the barber’s assistant and then you flash forward 20 years later and she’s a hairstylist and she ministers to people that are in her chair. … I created the vignettes to create a connection from the past. Something that you would see in the present and how those things influence each other. So, I set off those sections that way. I think I have six sections, plus the epilogue. So, that was one thing. The other thing was I wanted it to be somebody reviewed it and they called it intertextual. I didn’t know what that meant at the time, but I was intending to do that without having that language for what it was. I was trying to connect something that happens earlier in the book to something later on. An example of that and I always like to give examples so you know what I’m talking about. You see the scene where Marisol is healed, they’re dancing and they’re getting out of her grief. She’s getting out of grief by dancing with Victoria and her friend on the carpet. So, that happens in one chapter earlier in the book. Later on when Victoria is sad [on] Mother’s Day because she’s remembering the postpartum depression that she had, Victoria’s remembering that on that Mother’s Day and she’s down, Marisol … has her look up and try. She goes, “Let’s dance, comadre.” Marisol who was comforted by Victoria previously is now the comforter. So, I wanted it to be intertextual in such a way. That scene where they’re dancing in the carport of Victoria’s house on Mother’s Day is a call back and reminiscent of them dancing in Marisol’s house on the carpet. I try to link them that way thematically so that you could say, ‘Oh, this is all weaving together as one big story.’ And that, ‘What happens over here, matters because it’s gonna happen over here and it’s gonna help someone else.’”

You can hear into every room and every corner of this book. Was that intentional, what senses did you focus on when you set out to write your stories?

“Wow, what senses do I want? I want the reader to feel like they’ve been invited to the carne asada. They’re there. You know what I’m saying? They’re at the pachanga. They’re at the quinceañera. They have been invited. So, you see the family but you’re a friend of the family. When I sign books I say welcome to the family. … When you go to a party … you go somewhere that the senses come at you. It’s what you notice first. I try to be a very visual writer. What do the fajitas look like? What does the Polish sausage look like? It’s shiny. It’s greasy. What do people smell when they walk in? And then with that sensory input that I’m putting, I’m trying to put the reader right there. My struggle as a writer is I don’t do a lot of interiority stuff where the character’s thinking. I do some of that but that’s because my editor pulled that out of me. I’m much more visual. I’m much more sensory. I’m trying as a writer … to grow and to become more in the headspace of my characters. … The other thing I would say too is the sounds. In the book there’s always music playing somewhere in most of the chapters … whether it’s at the party, somebody’s got a boombox on, whether it’s a quinceanera, whether it’s Dina at her house listening to the records and the records have played-out. Music is a very important part of our culture and I wanted to capture that. So, we’re talking, anything from tejano, conjunto to … I’m writing about new wave music now a little bit, The Cure, The Smiths, all these things are a constant in our lives. There’s the music and then the other thing too, is that … when you’re at a party, the voices of people to me are very important. If I’m at a party with my family, I can hear someone’s laughter in one corner of the house and know, ‘Oh, that’s Tia Mari.’ I can hear someone sneeze on the other corner of the house and say, ‘Oh, that’s my Tio Ralph.’ And so what I did was, the way I kind of captured those sounds, is I would reference these things so that it’s never quiet unless I intend to tell you it’s quiet, like in Dina’s house, it’s very quiet. Otherwise, there’s always a cacophony, there’s always family around and that’s a very comforting thing for those of us who have big families.”

Your work involves many supernatural and spiritual elements that feel so true to valley life and our culture. How did you strike that balance?

“I’m a Christian and in my family you have Born Again Christians, you have Catholics, charismatic Catholics and then in the community, there’s curanderismo and there is brujeria. So, you have a collision of four, I mean many more, of course, but I captured four different spiritual traditions. Again, brujeria, curanderismo, Catholicism and Evangelical Christianity and not the nationalist side of it. I’m talking about the home-churches that you see in the barrios. So, how I approached that was … I’m trying to tell a story of grace, of redemption and coming from where I’m at as a believer. But I have to approach it in such a way that it doesn’t come off as preachy and I kind of wrap it up in such a way that it’s through the culture because I think, honestly, if you’re writing about the valley, I think the most honest thing someone can do to write about the valley … is you can’t leave that out because that is a huge part of of this community. I think for me to divorce that and to not write about spirituality, it’s not true. It’s not true to the family I’m writing about. For my family, It’s a big deal for us. I mean, you know, I’m on a thread with my family and they’ll send verses out. We’ve been to Zoom’s to pray and stuff like that. So, it’s a big deal. It’s a big deal to us. But what I wanted to do was show these things in such a way that I’m not writing a book that’s going to be in a Christian bookstore. I’m writing a book about a family that happened to have these beliefs. And then the other thing that I wanted to make sure I was doing, too, was like, how do those things collide and push up against each other? So, you have a character like Victoria who represents one side of the spectrum as far as religion goes and then you have the other side where this friend thinks that, the out there side, that she thinks Selena’s music is healing her comadre. So, you have all these different spiritual aspects that clash together, and to me, that’s very fascinating to me–how that all works in the valley.”

So, you have neurodivergent characters in your book whose stories are told with a lot of care. How do you set out to write these characters?

“Oh, I love every character. I have to start with love. If I don’t love the character, if I don’t have some compassion for them, it’s not going to come off right. It’s not going to come off well, and so, even to my antagonist like Contreras, you know, the brujo, I love him. He’s the so-called villain of the story because if you read the book and spoiler alert, he has cursed the family, but you find out that it’s not right what he did, but he has a good reason. I mean he has his reason anyway, I should say, for doing it. So, how I approached every single character—and thank you for saying that because that affirms what I’m hoping to do—is create each character with care. I try to write them in such a way that if I’m writing about you … and you’re reading your character. Like I may show you with your flaws, right? But you will know that I’ve done it in such a way that I care about you. So, you know any one of these characters in my head, they’re not real people but I have relationships with them. … If Maggie is reading her story, how is she going to feel about me writing her story? Is she going to see that I was critical with her or that I did show her flaws? But I did so in such a loving way that I also showed her strengths, right? Because I believe nobody should be treated that way in life. So, I kind of reach it that way in fiction. … I have to start with love and then I have to do it in such a way that as they’re written, like I said, if they themselves were reading about themselves, how would they respond? So, I’m thinking of them as I’m writing them. That’s a great question. I love that question.”

You have a very large cast of characters with very different personalities and experiences. How do you find inspiration for characters that you want to write?

“Oh, wow, that’s a big one. Yeah, because there’s a lot of people in that book. So, as a writer we are witnesses. And so being a witness means paying attention. And so as an author I pay attention to people around me. None of the characters in that book except for maybe one or two are exactly like who they are in real life and I won’t say who but they’re all like pastiches. My inspiration is [that] I will hear someone say something. So, I’ll give an example, Maggie. She’s the hairdresser, right? I had a hairdresser that talked like her and then at another point I had another hairdresser that she, the way she did hair, was just like Maggie. And so, I’m always inspired by people. I walk around, I listened to them. I pay attention to the nuances of not just how they talked but how they navigate the world. Even when I was a little kid, I always paid attention to people and I remember stuff about people so I put all those things together and I create characters. I create pastiches of people. Then the other thing that’s very important to me as an author is I use a lot of first-person narrators because I believe that everybody has their own voice. I try very hard to make each of those individual narrators sound different so that … you could just pick up a story and you know this story is being narrated by Cirilo. I can tell his word choice, the way he structures things, his syntax, all of that. Then I can pick up another story and say, ‘Oh, this is little Gonzalo narrating this story.’ He’s more matter-of-fact. He tells it like it is. He just shows what he sees and maybe he gives a little history. So, in that way because people have their own voice, that inspires me to write the characters in such a way that when I’m narrating using them, writing them down in their narration is that I’m giving them the same voice.”

So you deal with a lot of themes in the book. The themes of loss and healing really stuck with me. Papa Tavo and his health and Dina and what she does with the kind of reckoning that goes down. How did you come up with that? Did you set out wanting to write about any theme in particular?

“I set out to write about themes that we don’t talk about as people as a whole. Right, so, mental health. It’s not something in our community that I think we talk about enough. And I think we’re getting better about it. But that wasn’t something that we talked about … when I grew up, [it] wasn’t something we talked about. So, that’s one and then another theme is loss and healing. I think in too many stories that I read, we’re not talking about those things and those things are important to me because of my faith and who I am. … I believe in miracles, I believe in healing, I believe in those things. So, I like to write about them and I like to show people that there’s more going on under the surface than we know about. So, that’s kind of like the spiritual side of it. The other thing, too, as far as themes go, is … people have told me I write men well. Because my male characters are nuanced and you read a lot of like Chicano fiction, Latino fiction and fiction by a lot of authors Latina, Latino, otherwise and the men are sometimes, they’re more one-sided, because you have the patriarch and he’s machista … and this guy’s out there cheating and so you have these stereotypes. But I’m like, ‘You know what, that doesn’t encompass who I am.’ It doesn’t encompass a lot of the men I know who helped raise me. So, I wanted to honor that and then the other part of that, in that theme, is like, these people are not perfect. But there’s a lot of good qualities in them. You know, there’s men who are providers that work very hard for their families that nobody’s writing about. You see them in life, but you don’t see them in fiction. So, I wanted to capture that. And then there’s also a nurturing side of Latino men, Chicanos … that we all don’t see. So, I try to capture that, like in the scene with Gonzalo where he picks up his baby. The nurse, the lactation specialist, has told Gonzalo and Victoria that they need skin to skin contact. At first Gonzalo is like whatever, he laughs at it, makes fun of it. But Victoria sees him. He’s got his shirt off and he’s carrying his baby and soothing him. So, there’s also a maternal and nurturing side to men that I wanted to capture. Those are just a few things. This is … forgiveness, redemption, all of those things I think we need to see more of in fiction. So, that’s what I wanted to do.”